For a long time now, I have been maintaining that America’s cruddy monetary system was headed toward a crack-up. Of course, it’s always impossible to predict the exact timing of such a crack-up but it’s not difficult to predict that at some point in time, the crack-up will occur.

For a long time now, we have seen out-of-control federal spending on the welfare-warfare state, spending that far exceeds the amount of tax revenues being collected by the federal government. The difference has been borrowed. The federal government’s debt now exceeds $31 trillion. Assuming that the debt will be repaid, that sum will be collected from taxpayers. Each taxpayer’s share of the debt is $246,000.

There is no end in sight to this out-of-control spending and debt. Each time the debt ceiling is reached, it is raised. Each year another $1 trillion or $2 trillion is added onto the debt.

Moreover, there is virtually no possibility that any group on the federal dole will permit any reduction in its dole. This is particularly true with respect to the three largest programs involving federal largess — Social Security, Medicare, and the national-security establishment.

Adding to this toxic mix is the decades-long debauching of America’s paper money. Decade after decade, the Federal Reserve has been expanding money and credit and, in the process, reducing the value of everyone’s money.

Whenever the Fed’s monetary debauchery begins manifesting itself in a big way through soaring prices in the economy, the Fed then throws the economy into one of its periodic Federal Reserve-induced recessions, which inevitably throw various sectors of the economy into bankruptcy.

Once the Fed has inflicted a large amount damage with its recession, it then embarks on another round of “easy money,” which begins the cycle all over again.

The principal way the Fed induces its recessions is by raising interest rates. That’s what it has been doing in a major way for the past several months.

The assumption has been that the primary victims of the Fed’s actions would be building contractors. The Fed’s attitude toward the housing industry has always been, “Tough luck. That’s the price of living in a free society.” Thus, as the housing market started slowing down, the Fed couldn’t care less. In fact, it considers that to be a measure of its success in “fighting inflation.”

This time around, however, it has become clear that the tech industry has also fallen victim to the Fed’s interest-rate antics. But like with the construction industry, the Fed has been indifferent.

Notwithstanding the pain that the Fed’s monetary policies are having on these particular sectors, the Fed recently signaled that it intended to resume its high interest-rate policies owing to soaring prices arising from the Fed’s previous round of “easy money.”

Not so anymore, however. Investment analysts are now predicting that the Fed will either cease or significantly slow its interest-rate hikes.

What happened to bring about this shift? Well, this time, just like in 2008, it turns out that the Fed’s interest rate-antics are hurting not just the construction and tech industries, but also hurting the banking industry — big time.

Now, it’s one thing when construction firms or tech firms go bankrupt. No big deal. But it’s quite another thing when banks start going under, like what happened over the weekend with Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank, two extremely large banks.

The demise of those two banks has caused the Federal Reserve to react completely differently than it has to the demise of construction firms and tech firms. That’s because the Federal Reserve is composed of — yes, you guessed it — bankers! The bankers who run the Fed and the bankers who run the banks are comrades. The Fed isn’t going to let its banker buddies go under. Their banker comrades are different from the people in the construction industry and tech industry. Their banker comrades are important.

As I have long maintained, the federal government is capable of handling a few bank failures. But their policy has always been to not let banks simply go under. Instead, their policy has been to absorb these failed banks into the overall banking system.

That’s a long-term prescription for disaster because they inevitably end up with an increasingly weakened overall banking system. As I have long maintained, over time those chickens will, at some point, come home to roost.

Here’s some of what I have been writing:

2017: “Imagine a massive economic and monetary collapse akin to the Great Depression. A massive run on the dollar. An industry-wide banking collapse, one where there isn’t enough money to honor the FDIC’s commitments. Massive bankruptcies and unemployment.”

2017: “On top of it all, suppose there was a severe economic crisis, one entailing a plummeting stock market, a major drop in the value of the dollar, and an industry-wide banking collapse, much like what happened during the Great Depression.”

2022: “But what happens if there is a nationwide banking collapse? The amount of money in the FDIC’s insurance fund is enough to cover losses in several individual banks. But it doesn’t even come close to being able to do that in the event of an industrywide banking collapse.”

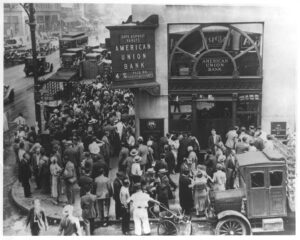

2022: “But what happens if there is a nationwide banking collapse? The amount of money in the FDIC’s insurance fund is enough to cover losses in several individual banks. But it doesn’t even come close to being able to do that in the event of an industrywide banking collapse. If that were to happen, then the bank-run phenomenon would surface because panicked depositors would be rushing to get their money out of banks, knowing that there would inevitably be depositors who would be caught holding the bag.”

We witnessed an old-fashioned bank run over the weekend with those two failed banks. Panicked depositors were doing everything they could to get their money transferred out of those two banks. Some succeeded. Others did not. Fearing that the bank-run phenomenon would spread to other banks, federal officials have promised to bail out all uninsured deposits in both banks.

Is this just an isolated banking problem? Or is this a crack in the cruddy, dangerous, and weakened monetary dam? Time will tell.